FORCED LANDING OF A LOCKHEED

HUDSON

AT ANNESLEY POINT, NT

ON 14 MARCH 1943

![]()

Lockheed Hudson A16-242 and a second Hudson took off from Batchelor Airfield at 2055 hours Z time on 13 March 1943 (Z time or Zulu time is the same as Greenwich Mean Time) to carry out an anti-submarine patrol ahead of HMAS Latrobe which was escorting Darvel and Burwah. At 2215 hours Z time on 13 March 1943, when approximately ten miles South East of Malay Bay, and five minutes after switching to auxiliary tanks, both motors cut out completely at 2,500 feet. The pilot, Flying Officer Thomas Saunder Graham (400982), immediately switched to the wing tanks and switched on the auxiliary fuel pumps. Three wing tanks were tried successively without result. The position of the ignition switches was checked, mixture was put to full rich, pitch into fine and throttles wide open. The motors still failed to recover. The pilot then jettisoned the bombs.

Photo:- ADF Serials and AWM 027611

Lockheed Hudson A16-242

The pilot noted two semi-clear patches for a possible emergency landing, with one patch being larger than the other. The rest of the countryside was heavily timbered. F/O Graham attempted to land on the larger patch but the aircraft had excessive speed and height. F/O Graham managed to lift the aircraft over some heavy timber, grazing the treetops and then forced landed wheels up, on the smaller patch of clear ground about two to two and a half minutes after both motors stopped. The Hudson slithered on its belly for about 100 yards and turned 180 degrees and came to rest. The 2 Squadron ORB states that the aircraft crash landed at Annesley Point at approximately 0001 hours Z time on 14 March 1943. The times mentioned in the above paragraph were based on the times shown in the Confirmatory Memorandum dated 27 March 1943 from No. 2 Base Personnel Staff Office at Birdum, N.T.. There appears to be some discrepancy between the times in the two sources. The date of the forced landing is either just before midnight Z time on 13 March 1943 or just after midnight on 14 March.

There were no injuries amongst the following five crew members:-

Flying Officer Thomas Saunder Graham (400982)

Sgt Noel Arthur Adamson (401639)

P/O Alan Gordon Shepherd (416156)

Sgt Colin Stuart Storrie (406762)

Sgt. Alistair Gollan McKittrick Matheson (416691)

The Aircraft Accident Data card only shows four crew members with P/O Shepherd not shown. The 2nd Squadron ORB for 14 March 1943, shows Lockheed Hudson with the names of five crew members as shown above.

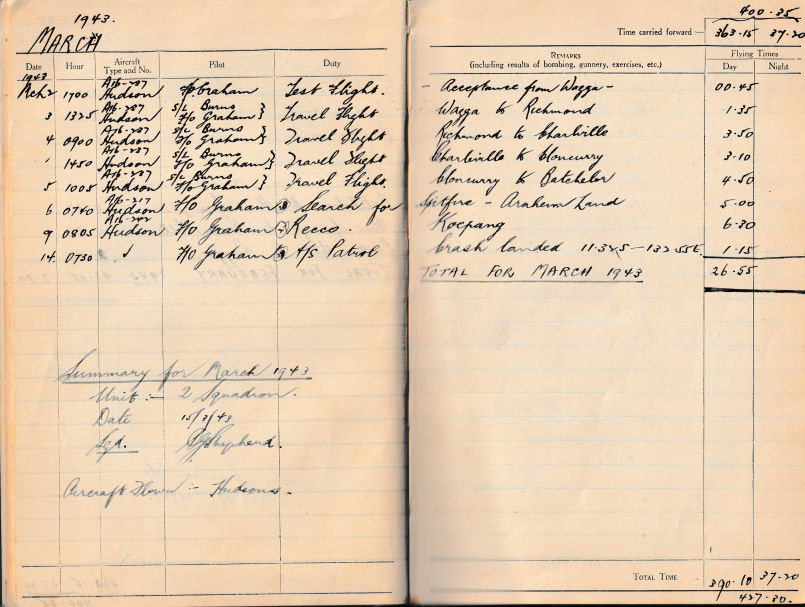

Via Graham Shepherd

Logbook entry for P/O Alan Gordon Shepherd (416156)

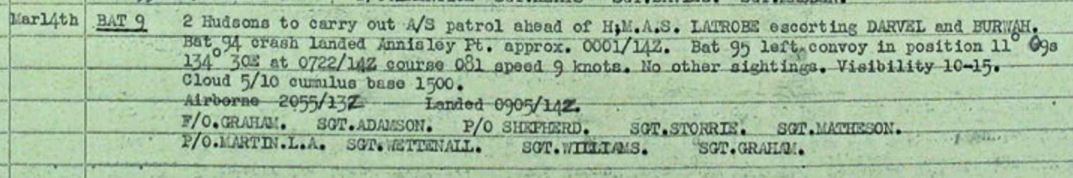

File:- NAA

ORB entry for 2 Squadron RAAF

Damage to the aircraft as as follows:- "Damage was sustained to all leading edges - wings, tail-plane, fins. One wing-tip was practically wiped off, both props damaged in all blades, nose and side perspex and lass extensively damaged. The belly gun mounting was badly damaged as were the oil radiators. The left hand front petrol tank was leaking."

After repairing the broken radio aerials on the wrecked Hudson, they were able to re-establish contact with their base and advise of their forced landing and their approximate location. A Vultee vengeance dropped instructions and supplies to them by parachute. They were instructed to head towards the coast. By the time they setout for the coast there were only four hours of daylight remaining. They travelled 7 to 8 miles and camped on a relatively dry spot for the night. Their attempt to use a parachute as a mosquito net was only partially successful.

The next morning they made slow progress through mangrove swamps and finally reached the coast some 5 miles east of Annesley Point where they were to rendezvous with the Navy vessel. The crew members waded in the sea beyond the mangroves towards Annesley Point, but after 1/2 mile the encountered a creek about 30 yards wide. A small shark, a stingray and may Portugese-man-of-war were seen in the creek. After shedding non essential heavy gear such as revolvers, flying boots, etc they made a safe crossing of the creek.

At this time, a Vultee Vengeance flew over them, then flew out to sea to warn the rescuing vessel, and then returned and dropped the following message:-

"Rescue ship close. Build large fire."

As a consequence they no longer needed to make their way any further to the Point. They built a large fire. A motorboat arrived and at 1600 hours K.L. time on 15 March 1943, they boarded the "Southern Cross". They arrived in Darwin at 0330 hours Z time on Thursday 18 March 1943.

The following is a replica of

latter sent by Alan Gordon Shepherd to his wife Una.

This letter can be found on

"Shep's Place"

along with lots of other information.

| From Alan to Una X 416156, P.O. Shepherd A.G., Group 662, DARWIN. 17 Mar 1943 Last Sunday we set out in our lovely aeroplane on a job. After being airborne for an hour or so both engines gave up the ghost and left us, so to speak, without means of support. Tom hurriedly jettisoned our bombs, we all jammed ourselves into what we considered the safest positions and within a couple of very long minutes Tom had miraculously landed us in a swamp about ten miles inland from the Australian coast and a good 150 miles from any white-man's habitation. Getting down safely was an exhibition of very excellent airmanship on our pilot's part, in the first place, and a marvellous combination of fortuitous circumstances, which we can call the guiding hand of God more than "luck". For some reason he doesn't know himself, Tom was flying a thousand feet higher than usual, just in the right place was a small swamp clearing with heavy timber thick around it for miles and we just made it, taking the light top branches off a couple of trees and clearing heavy trunks that we couldn't have got through by just a foot or two. We were all scratched and one or two a little bruised, but not one of us was really hurt at all, though the poor plane was properly wrecked. Her flying days were over, poor girl. Fortunately, the W/T equipment was only slightly damaged and within an hour we had repaired it and were in communication with our base. They cheered us greatly with the reply that help was on the way. We built beacon fires at a safe distance from the petrol and oil covered wreck and sat down to wait and review the situation. You may guess that the shining light that filled our minds was amazed gratitude at our good fortune in being alive to tell the tale. Now that we had been able to report and give our position to base we knew that, although there was some pretty stiff walking and some hardship in the way of mosquitoes, etc, in front of us, we would be rescued before many days were up. Soon we heard a plane, lighted our beacons, and were located and succoured by provisions of water, bread and butter and good old bully beef together with a message to walk to a certain point on the coast and wait the arrival of a naval vessel, which had been sent to pick us up. We set out on our trek at 1630 hours, carrying emergency rations, two gallons of water, a compass and map, the bread and bully beef and the silk from a parachute, which we hoped would provide us with a tent, which would reduce the mosquito menace to a minimum during our camping halts. Gosh, that walk was a nightmare. For hours we walked through water up to our knees, at every step our feet sank into the mud and stinking water filled our flying boots and made walking a torture. We waded through creeks up to our waists and tripped over vines, which seemed like blooming octopus tentacles reaching out for us. At 10 p.m. we decided it was time to call it a night and we lit a fire, made what we thought was a mosquito-proof tent out of our 'chute and prepared to go to sleep. Mosquito-proof! My eye! Goodness knows where the mossies did come in but come in they did - in their thousands. I think that their noise was worse than their bites. We set off again at 8 a.m. calculating that we were two miles from the beach. Before long we came to a wide belt of mangroves and spent a lovely couple of hours clambering over mangrove roots and stinking bog. Then we came to a river about sixty feet across and probably ten feet deep. Not liking the thought of crocodiles, which abound in most of these rivers, we decided to follow it to the sea, which we did. However, then we found ourselves a couple of miles away from our rendezvous and had to swim the river after all. In crossing we lost a couple of revolvers and one or two other things when our Observer tried to throw a bundle over and badly misjudged the distance. We did get our water and our provisions over though, which was the main thing. The river was a bit more than brackish and possibly fever-ridden as far as we were concerned, so we were rationing our water in case the ship didn't arrive as arranged. The ship was not there, but another of our planes found us and signalled to us with an aldis lamp that she was a couple of hours away and for us to light a fire to guide her to us, which we did. About this time it started to rain heavily. We were fortunate to find a couple of native mia-mias, (little huts made of saplings and paper bark) where we were able to shelter. There were no signs of abos having been there for some time. About 1530 hours the ship arrived and took us aboard - and we were thankful. Weren't we amazingly fortunate? First of all to come out of the crash alive and unhurt and then to be taken aboard ship 30 hours afterwards. The captain, officers and men are treating us very well. They were able to get to us so quickly because they happened to be on a job in the neighbourhood and were wirelessed to pick us up. The journey back to Darwin will take about three days. Because of the dangerous waters we travel only during the daytime and anchor at night. There are about a dozen abo boys, three abo women and two dear little tarbaby piccaninnies on board. The boys are Melville Islanders, said to be easily the finest type of abo in Australia. They seem more intelligent than most, but are just like children all the same. They are clean and cheerful workers. They are employed by the Government as aeroplane spotters, trackers, etc. When we anchor at night they go ashore with their spears and raffia baskets and come back with fish and turtle eggs for our meals. Scrambled turtle eggs taste very nice indeed. Last night the black boys dug up some cobbers on the mainland, we all went ashore and they turned on a corroboree for us. They are great actors and portrayed in their dancing little plays about hunting buffalo, crocs, wallaby, fighting between the tribes and so on. They rather shocked us with one wedding dance, which was quite lurid in its uninhibited revelation of wooing and winning. In none of these dances do the gins take part except to sit well in the background chanting and occasionally rising and doing a sort of shuffle-on-the-spot as an accompaniment for their lords and masters. We should probably be back on Friday. It is hard to realise that what we cover in an hour by air takes about three days by sea. The routes the ships take are governed by coastlines, shoals, reefs, etc. Several times we have sighted aircraft in the distance. They have all turned out to be our own planes, thank goodness. The niggers have astounding eyesight and see planes long before anyone else. 19 Mar 1943 It was a funny feeling to think, "In a few seconds I may be dead". None of us was conscious of fear, though for a few nights Tom said he was haunted by visions of the trees around the edge of the little swamp looming up before his eyes every time he closed them. There was one young "boong" named Ginger Mark 2 - as black as the ace of spades - who wouldn't go ashore at one place because "Longfeller Mary, she sit down along this place. Last time she killen me here" (placing an anguished hand on his behind) "she catchem hold er me, she chasem me, me go along shore. She want to marry me. No sir, me stay alonga ship." And although the boys teased him unmercifully, young Ginger Mark 2 stayed aboard where Longfeller Mary couldn't catch him. Later.

|

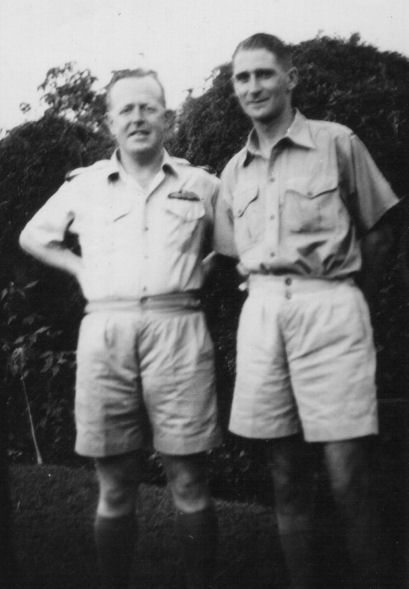

Photo:- via Graham Shepherd

Flying Officer Thomas Saunder Graham (400982)

with

P/O Alan Gordon Shepherd (416156)

Tom Graham and Alan Shepherd were great friends during and after the war even though Tom and his family lived in Melbourne and Alan and his family lived in Adelaide. Alan's son Graham was named after Tom Graham. He was either going to have Graham or Thomas as his first name after his father's pilot during WWII.

Photo:- ADF Serials

Stated to be the wreckage of Lockheed Hudson A16-242

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I'd like to thank Graham Shepherd for his assistance with this web page.

Can anyone help me with more information on this crash?

"Australia @ War" WWII Research Products

|

© Peter Dunn OAM 2020 |

Please

e-mail me |

This page first produced 2 October 2021

This page last updated 04 October 2021