11 SQUADRON RAAF

IN AUSTRALIA DURING WW2

![]()

11 Squadron RAAF was formed at Richmond in New South Wales on 21 September 1939 under the command of Flight Lieutenant J. Alexander.

11 Squadron moved to Port Moresby in New Guinea on 28 September 1939 to carry out survey work for suitable landing sites in the region. The Squadron was equipped with two, four-engine "C" Class Empire Flying Boats and two Seagull, Mk5 amphibians. RAAF Marine Section boats, crews and facilities would have been in place before the arrival of No.11 Squadron in Port Moresby. They were also involved with assisting Coast Watchers, and carrying out reconnaissance and intelligence work in the area. At that stage they comprised 8 officers and 23 other ranks.

In May 1940 they assisted the HMAS Manoora to search for the Italian motor vessel Romolo. The Squadron received its first Catalina on 19 March 1941. By the end of June 1941 they had 4 Catalinas and 4 ex QANTAS and Imperial Airways S23 "Short" Empire Flying Boats (see below).

| A18-10 | Centaurus |

| A18-11 | Calypso |

| A18-12 | Coogee |

| A18-13 | Coolangatta |

Wing Commander C.W. Pearce took over as Commanding Officer of 11 Squadron on 17 May 1941.

20 Squadron was formed at Port Moresby on 1 August 1941 and on 14 August 1941 they took over the Catalinas that 11 Squadron had leaving them with their Empire Flying Boats. 11 Squadron received some more Catalinas in November 1941.

Squadron Leader J.A. Cohen took over as Commanding Officer on 28 August 1941.l

On 25 November 1941, Catalinas A24-11 (11 Squadron) and A24-14 (20 Squadron) were attached to Western Area to search for survivors from HMAS Sydney which had been sunk by the German Raider Kormoran.

On 8 December 1941, one day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Catalina A24-15 crashed into a hill during a night time take off at Port Moresby. All on board were killed. Earlier that day Japanese aircraft had been sighted over Kavieng and Rabaul.

Bob Ruegg was one of 25 members of the 27th Bomb Group who were evacuated from the Philippines along with seven pilots of the 24th Pursuit Group on board QANTAS flying boat A18-10 "Centaurus" of 11 Squadron RAAF. The aircraft was piloted by Squadron Leader Norm Fader and co-piloted by Squadron Leader Mike Seymour. They had departed Darwin on 23 December 1941 in RAAF short Empire flying boat which travelled to Brisbane via Groote Eylant, Townsville, Rockhampton, arriving at the Hamilton Reach of the Brisbane River on 24 December 1941. They landed on the Hamilton Reach of the Brisbane River near the ships of the Pensacola Convoy. The arrival of the 27th Bomb Group and the 24th Pursuit Group pilots onboard Centaurus was commemorated on 15 August 1998 when a Memorial was unveiled at Bretts Wharf Seafood Restaurant at Bretts Wharf, Hamilton in Brisbane.

Six Catalinas from 11 Squadron attempted their first attack on the Japanese on 12 January 1942. Three aircraft refuelled at Kavieng and another three at Lorengau. They were unable to reach the target due to bad weather. Three days later they made another attempt and again bad weather hampered their efforts. One Catalina managed to make an attack but results could not be confirmed.

In January 1942 a Catalina from 11 Squadron was attacked by 5 Japanese fighter aircraft. The Catalina caught fire and crashed. The only survivor from this incident arrived back in Port Moresby ten days later. The Japs landed at Rabaul and Kavieng on 22 January 1942 causing Australian forces to withdraw to Port Moresby. 11 Squadron then started to carry out night time bombing raids on Japanese positions.

The Japanese carried out their first aerial attack on Port Moresby on 3 February 1942. By 20 March 1942, Port Moresby had been attacked 16 times.

On 16 February 1942, the following ex QANTAS Empire Flying Boats were reassigned from 11 Squadron in Port Moresby to 33 Squadron which had just been formed in Townsville:-

| A18-10 | Centaurus * |

| A18-11 | Calypso |

| A18-12 | Coogee ** |

| A18-13 | Coolangatta |

Squadron Leader F.B. Chapman took over as Commanding Officer of 11 Squadron on 30 April 1942.

Due to increased Japanese naval activity at Rabaul and continuing Japanese attacks on Port Moresby it was decided to move 11 Squadron to RAAF Flying Boat Base at Bowen in north Queensland on 7 May 1942. Catalina A24-24 was believed to be the first Catalina to arrive in Bowen, about ten days before 11 Squadron and 20 Squadron formally relocated their operational activities to Bowen from Port Moresby, which was no longer safe from Japanese attack.

It was at the time of this move to Bowen that the Battle of the Coral Sea took place between 4 May and 8 May 1942. 11 Squadron Catalinas carried out many reconnaissance patrols and provided much sought after intelligence on Japanese activities during this tense period.

11 Squadron completed its move to Cairns in tropical far north Queensland on 11 November 1942. Catalinas from 11 Squadron had actually begun flying "Run M" missions from Cairns since 5 November 1942. These were night time attacks on Japanese ships and submarines along their routes to Lae, Salamaua and Finschhafen areas.

On 6 January 1943, an 11 Squadron Catalina attacked a Japanese convoy and sank a 12,000 ton transport ship with three direct hits. Wing Commander R.A. Atkinson took over as Commanding Officer on 25 January 1943.

On the nite of 2 March 1943, a Catalina followed a Japanese convoy moving north of Vitiaz Strait toward for the Huon Gulf heading for Lae. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea took place the next day on 3 March 1943.

On Saturday 27th March 1943 at approximately 0512 hours Douglas DC3 (C-47) VH-CTB, A65-2 (A30-16) of 36 Squadron, based in Townsville, was involved in a fatal accident at Archerfield. The crew of four were killed as were all passengers comprising 17 Australian and 2 American personnel. One of the Australian passengers killed was LAC Kenneth Owen Paton of 11 Squadron RAAF.

Air Commodore A.H. Cobby took over as Air Officer Commanding North-eastern Area (AOC NEA) from Air Commodore Lukis on 25 August 1942. His North-eastern Area Headquarters were located in the old Commonwealth building in Sturt Street, Townsville. In April 1943, Air Commodore Cobby had the following RAAF Squadrons under his command:-

| 7 Squadron | General-reconnaissance | Beauforts | Ross River airfield, Townsville |

| 9 Squadron | Fleet cooperation | Seagulls | Bowen Flying Boat Base |

| 11 Squadron | General-reconnaissance | Catalinas | Cairns |

| 20 Squadron | General-reconnaissance | Catalinas | Cairns |

On 11 April 1943, 11 Squadron started operations in North Western Area attacking a Japanese staging base at Babo.

RAAF PBY-5 Catalina, A24-36 of 11 Squadron RAAF, crashed into Cairns harbour on 13 April 1943 on return from a night-time search patrol. They had flown for 23 hours 23 minutes and ran out fuel. Six of the eight crew members were killed. The aircraft was damaged beyond repair.

On 22 April 1943, 11 Squadron carried out its first of many mining operations over the next two years. Their last mining mission was on 31 July 1945. Between April and June 1943, 11 Squadron laid mines in the New Ireland and Admiralty Islands. In July 1943, they commenced mining harbours and shipping routes in the Netherlands East Indies.

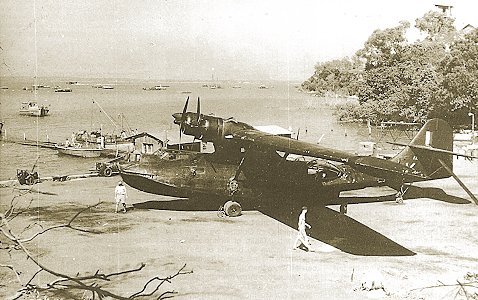

11 Squadron RAAF Catalina at

Doctor's Gully, Darwin in July 1945

11 Squadron RAAF Catalina at

Doctor's Gully, Darwin in July 1945

Combined Operational Intelligence Centre personnel based inside Castle Hill in Townsville would encipher and decipher secret messages to the Coast Watchers in the New Guinea area. They would change their codes every hour. One particular Coast Watcher named Paul Mason who was an ex British Artillery man was located on Bougainville near Faisi and Buin Islands. This was in the area where the Japanese fleet would assemble. He would send signals to COIC Townsville who would then send Catalinas from 11 Squadron and 20 Squadron up to the area to bomb the ships. Mason would give them eight figure map co-ordinates which would allow them to very accurately pinpoint the location of the Japanese shipping. One day a signal was received from Mason to indicate that the Japanese had landed some dogs to help track him down. The Japs knew he was there somewhere. A Catalina was dispatched and it apparently managed to hit the dog's enclosure. Mason was moved and eventually evacuated from Bougainville.

Wing Commander R.F.M. Green took over as Commanding Officer of 11 Squadron on 24 June 1943.

RAAF PBY-5 Catalina, A24-52 of 11 Squadron RAAF crashed into Cleveland Bay at Townsville, Queensland while attempting to land in rough conditions at 1648/Z hours on 7 September 1943. It was returning from Merauke. After touching down on the water it travelled a short distance and struck a large wave and sank by the bow. Of the nineteen passengers and crew on board seven crew members and six passengers were killed.

Short

‘Empire’, VH-ABB ‘Coolangatta’ of QANTAS.

Impressed by RAAF as

A18-13

and

allocated to 11 Squadron RAAF. It

was returned to QANTAS

on 13 July 1943, but crashed in Sydney Harbour on 11

October 1944.

Squadron Leader G.W. Coventry took over as Commanding Officer of 11 Squadron RAAF on 13 March 1944. Wing Commander W.K. Bolitho took over form Coventry on 8 June 1944.

11 Squadron relocated to Rathmines in New South Wales on 10 July 1944. 11 Squadron continued its submarine reconnaissance duties, searches for Jap shipping. 11 Squadron continued mine-laying missions in forward areas in December 1944. Twenty five Catalinas from 11 Squadron and three other Squadrons combined to lay mines in Manila Harbour to support the Allied landings in the Philippines. 11 Squadron Catalinas flew 9,000 mile missions to carry out this mining in Manila Harbour. The Catalinas from 11 Squadron returned to Rathmines at the completion of these missions on 19 December 1944.

Squadron D.R. Lawrence took over as the Commanding Officer of 11 Squadron on 9 March 1945.

Five Catalinas were used on 6 September 1945 to transport personnel from Labuan Island back to Australia. A further six aircraft carried out similar work in September 1945.

Many crews left 11 Squadron from October to December 1945 due to postings and discharges. A signal was receive don 10 December 1945 indicated that 11 Squadron would cease to function from 20 December 1945. All of its aircraft were allotted on 7 February 1946 and the Squadron was finally disbanded on 15 February 1946.

Meg Dunn is researching her uncle Clifton Stuart Dunn who was a Flying Officer during WWII flying PBY5 Catalina A24-43 in 11 Squadron. Meg believes the plane crashed on Bougainville, where Clifton Dunn was later shot by the Japanese. An account of Clifton Dunn's death is mentioned in AE Minty's book titled "Black Cats". Clifton had been in 22 Squadron before joining 11 Squadron.

Robert Ballingall was in 20 Squadron and 11 Squadron, and was then posted to Rathmines as an Instructor Fitter Air Gunner. When the Japs started to be pushed back , 113 Air Sea Rescue was formed. Under skipper Wally Mills Robert Ballingall flew 160 missions (700 air hours). Their crew rescued 15 pilots from the sea .The Crew photo has only 5 of the original crew ,they are the ones named . Except Col Darling he replaced Bill Hasty who received a Bullet through the stomach during one of the rescues we did .

Malcolm Bridges is researching his father's RAAF service record (W/O Albert Thomas BRIDGES, Flight Engineer with 11 Squadron). There may be some connection with the crash of A24-39 at Port Stephens in New South Wales on 24 May 1943.

Bryan Sear's uncle was a member of 11 Squadron.

The story below was prepared by Group Capt Attie G. H. Wearne (Ret'd) DSO DFC, the former Commanding Officer of 20 Squadron RAAF. It refers to Catalina operations out of Darwin. Bill Burnett passed this story on to me and kindly obtained Attie Wearne's permission for me to publish it on my web site:-

|

RAAF CATALINA FLYING

BOAT OPERATIONS The saga of the Catalina in it's role of the RAAF'S LONG RANGE STRIKE AND MINELAYING FORCE had it's origin in Port Morseby in the early1940's. This was when 11 Squadron was re-equipped with the newly arrived Catalinas from America in March '41, and subsequently when 20 Squadron was formed, also equipped with Cats. Although the name of the squadrons never changed from General Reconnaissance (G R) an addition to this role did when six aircraft, three from each squadron, set out for the first raid on Japanese positions, staging through Manus and Kavieng respectively, to attack the Japanese Naval installation at Truk in the Carolines. From then on bombing attacks continued as the Japanese advanced southward until many targets such as Rabaul, Kavieng, Lae, Buka and Buna were covered. After heavy bombing attacks on Moresby made that base untenable, 11 and 20 Squadrons were relocated back to the mainland, first to Bowen then shortly after, to Cairns. From there they continued their mainly bombing operations until April '43 when part of their effort was allotted to the new role of "minelaying". On the 22nd of that month eight Catalinas from 11 & 20 departed Cairns, each carrying two 2000 lb mines to lay them in Silver Sound in the approaches to Kavieng. Thus began a new era for the "Catalina Force". In September '44, 20 squadron was relocated to a new base, East Arm at Darwin, from where it operated until the end of the war. At the same time 11 Squadron was relocated to Rathmines. Meanwhile 43 Squadron had been formed at Karumba, in the Gulf of Carpentaria, and relocated in April '44 to Darwin. At Darwin the unit was first housed on the Airfield but then moved to facilities at Doctor's Gully. A third squadron, number 42 also equipped with Catalinas, was formed about this time and located at Melville Bay on Arnhem Land just East of Darwin. The three squadrons formed number 76 Wing with Headquarters located at Doctor's Gully. After the introduction of mines in April '43 the bombing effort of the Catalinas would gradually decrease until the three squadrons were virtually totally committed to the minelaying campaign with singular success. However, the General Reconnaissance role was not lost and the occasional supply drop, sea reconnaissance, and sea rescue was undertaken. From Darwin the Catalinas of the Wing ranged over the whole of the then Netherlands East Indies (NEI) from Sourabaya and Banka Straits in the West, to Irian Jaya in the East and North to Borneo, the Halmaheras and the Celebes. All mineable harbours and roadsteads were sowed with mines and Japanese shipping was dislocated to the extreme. To reach some of these targets it was often necessary to refuel at forward staging bases such as West Bay and Yampe Sound. In addition American seaplane servicing ships in forward areas were used for this purpose. Towards the end of the war our aircraft staged north through the Philippines, at Leyte Gulf and Lingayen, to mine ports on the China coast including Hong Kong the Pescadores and Wenchow, 28 degees north latitude - the most northerly penetration of any RAAF aircraft in the war in the Pacific, and so made history. One particular highlight of the campaign was the mining of Manila Harbour when 27 Catalinas left Darwin to rendezvous in Leyte Gulf for the task. On this occasion the Wing was augmented by 6 aircraft of 11 Squadron flown up from Rathmines. The object of the operation was to bottle up the Japanese Fleet in Manila pending General MacArthur's invasion of Mindoro. This operation was completely successful and the object achieved. Another "Cat" unit, 112 Air Sea Rescue Flight, provided cover for Liberator strikes and various other tasks. RAAF "Cats" were the first to bomb Japanese installations after the downward thrust to New Guinea, they were the first to bomb Japanese occupied ports from the Netherlands East Indies to the China Coast, they were the first in and last out in the evacuation of our prisoners of war at the cessation of hostilities.

THE CONSOLIDATED PBY CATALINA. Considering that they were designed in 1935 the Catalina must be classed as the most successful and longest operating flying boat ever built. Powered by 2 Pratt & Whitney engines of 1200hp each, it had a range of 2500 miles (4000km), could carry a bomb load of 4000 pounds (1815kg), a wingspan of 104 feet (31.7m), a fuselage length of 63Õ 10 inches (22.4m) 17Õ11 (5.1m) high and a loaded weight 0f 35,420 pounds (16,100kg). Although slow in comparison to some of the land based aircraft its versatility made it ideal for the type of work it was to be engaged in. Many operations exceeded 22hrs in the air. Front line aircraft: No other RAAF aircraft fought at the front line of the Pacific War from the beginning of that war until stopped, 500 nautical miles from mainland Japan by the imminent dropping of the atomic bomb. During WW11 the RAAF had 168 Catalina flying boats on strength within Australia and the Western Pacific,68 of which were lost to enemy action or aircraft accident. From all Catalina Squadrons and support units 320 aircrew lost their lives in the defence of their country. That ground crew continued to do their work with exactitude and dedication is deserving of recognition. This has been seldom given except by the aircrews themselves whose lives depended upon their skills LEST WE FORGET |

The following Recollections by Dean H. Lees was forwarded to me by ex Warrant Officer Keith E. Hamilton (28561), a Flight Engineer with 11 Squadron and 20 Squadron. His Skipper was Squadron Leader. D H Lawrence. (dec'd). The comments in red in brackets in Dean H. Lees' Recollections are notes by Keith E. Hamilton. It was the result of a 'paper' search for any surviving crew members of the Liberator 'Doodlebug'. Five crew members of 'Doodlebug' were taken off a Japanese held island, 400 odd miles north of Darwin, by a Catalina Air Sea Rescue aircraft, on the 20th January 1944. The Catalina was captained by Flt. Lt. D.R. Lawrence of 11 Squadron RAAF, with Sgt. Keith E. Hamilton as 1st. Engineer.

This rescue was kept top secret as no-one wanted the Japanese to know that there were survivors, and certainly they did not want them to know that the rescue had been carried out. Keith Hamilton's interest in the matter has always been that the rescue location has sort of been mislaid over the years, mainly because it would appear it was listed in all documents as being from Seroea Island.

After much research including studying satellite photographs of the area, Keith is now almost certain the rescue Island was named 'Keke' and it's companion islet (possibly) to the North, was named 'Waroe'. These names were in Flt. Lt. Lawrence's log book amongst the 'Seroea' entries. Keith has concluded that his Skipper got those names from the natives that they took back to Brisbane with them, and who they returned to the island on the second trip three weeks later.

In 2004 Keith Hamilton was believed to be the only surviving member of the crew who carried out the actual rescue. Keith was at Tocumwal from October 44, until February 46, as a W/O Engineer Flight and Ground instructor, after completing Operational Tours with 20 Squadron and 11 Squadron on Catalinas.

|

RECOLLECTIONS : Serau

Island, (formerly Seroea) When we were in the water, our cover/escort tried to give us some help, by inflating their 'Mae Wests' and throwing them out to us. It turned out to be a generous but futile gesture, we could see the jackets falling as they came out of the aircraft, but the combination of the prop wash, - us being all beat up, - and our bobbing up and down in the large swells with only our faces out of the water, we just couldn't find them. In a short time our cover/escort had to leave, as their fuel reserves were limited. We could see the aircraft turning away, then their silhouette and engine noise fading out in the distance. As they left we had some apprehension about our future, which although real, didn't become overwhelming, because with our bobbing up and down, we could get glimpses of the island , maybe half a mile away, with people activity on a beach. Then in a little while we caught glimpses of canoes coming towards us. When a canoe reached me, I only had on my 'dog tags', throat 'mike', and G.I. white undershorts, - I probably made as sorry a looking catch as they had ever hauled from the sea. The big smiles on their faces were very welcome, although we weren't sure whether we were being captured or rescued! Immediately after helping us up the beach, the natives showed concern for our physical condition, and some of the women began very energetically, chewing a green leaf, after they had a good wad of leaf going, they would spit it out into their hand, and gently pat and pack it into our cuts. Maybe an hour or so later, they built a small fire , heated water and dunked coconut hemp/fibre in the now very hot water. After a bit of squeezing out they would hold the soggy mass on the now nearly dry and crusty leaf wad, until we were ready to yell ! This soak cleaned up the cuts pretty good ; after the clean up, they surprised us again, this time by sprinkling a fine sandy, tan and white looking powder on the cuts, and gently patting and rubbing it on each cut. My worst cuts were a 9 inch one, inside and above my right knee, a 2-3 inch one on my left wrist, a cut from my wrist watch, and some small ones around and above my left ear. After this series of 'First Aid', our cuts now looked clean and dry, with the edges all puckered up like corrugated roof metal. At this time I had no real pain, just sore and beat up. To me this 'First Aid' was an amazing and very effective medical procedure. Our concerns about the question of 'rescue or capture' were happily resolved during the first aid treatment by a couple of occurrences, first, the big smiles and gentle handling that we had received, second, the Second Engineer, Sawbridge, had been kept busy repeating at our rescuer's request, a pantomime of our mission against the Japanese. This was done with loud oral sound effects, and every time the bombs would drop, and go 'Boom' , they would laugh and cheer and wave for more. Later in the afternoon one of the villagers brought me a silk shirt, and what I would call 'mission boy shorts' (grey long john material with a draw string at the waist). We concluded that the limited concealment of my G.I. under shorts, were a source of embarrassment to them. Their modest behaviour was further demonstrated the next morning, when some of the women came down to the beach to bathe. With one hand up holding a dry sarong, they walked into the water, and splashed around bathing. Then they walked out of the water, and squirmed about putting on the fresh carried sarong, while removing the now wet worn one, -- all the while without exposing a square inch of skin. I still have the shirt and shorts, a very strong reminder of the tender care by a very special people. The beach that we were on was not sand, but water washed rock, and very hard to walk sit or lay on. It was formed by two ridges running 'V' shaped from inland to the sea, making a 'beach' 50 to 70 yards long at the waterline. These ridges on both sides left us with only a very limited field of view both seaward and upward. (Note. Though not mentioned, they would have had their 'backs' close to the near vertical inner side of the active volcanic vent, the whole area was filled with the pungent smell of sulphurous fumes which we noticed as soon as we came in sight of the islet the next morning, a small plume of smoke drifting from the vent well above the aircraft as we flew in almost at sea level.) This view restriction became important the next morning when we heard aircraft engine noise, and couldn't tell who , where, or what it was, but we didn't think that it was the Japanese, because the engines didn't have that out of sync. sound that the Japanese bombers usually had, but it could have been several of their fighters on patrol, so we decided to get under cover, --- then suddenly, - swoosh , swoosh, and gone, two fighters very low, almost directly overhead. ' Who were they' , we sure didn't know, from the very quick glimpse of the wing and fuselage markings, we believed that we had seen the Australian multi coloured, rather than the solid colour of the Japanese 'rising sun'. This quick consensus that the fighters were friendly, got us out into the open for their next pass, waving anything that we could get our hands on. Within a few minutes of the second pass, we spotted quite a ways out a Catalina flying boat, flying directly towards us from seaward, as he came closer, we saw a light flashing from his windshield, it was an 'Aldis' signalling lamp flashing us Morse code ! Our radio man and code expert, Sam Zelby, was one of the six not found, so the blinking light wasn't telling us much. Smith and I had some code training, so with Sawbridge , we tried to form a 3 man team, one to call out the dots and dashes, one to translate to the alphabet, and the third to write down or remember what had been transmitted, but even with the slow speed of the 'Cat', by the time we were organised, we only had a partially repeated 4 letters, RUOK or UROK, was this a question, or an encouraging statement? The Catalina, - Australian, after this signalling

and visual contact pass, circled left, to come around and land in front

of our beach, this was pretty much the open ocean, and the first contact

the Cat made, was with a swell that threw it back up, and then down he

came with such a splash, I thought we had company , instead of rescue !

It turned out that this type of open ocean landing was not entirely

unusual, and they had a kit aboard, that had wooden and rubber plugs for

filling holes left by 'popped' rivets in the hull. We learned later that he had paid the islanders 80 Dutch Guilders for each of us. We also found out later that they had tried to come for us the day before. (Note. It was another Catalina with a different crew, and a very experienced Skipper, Squadron Leader W.K. Bolitho, who, according to the official log book entries, had taken off from Darwin, but found that the seas in the crash area were running too high, and it was far too dangerous to attempt a landing). The next morning, the sea at Darwin was still running high, but we made it after 3 attempts with water breaking over the windshield. (Note. The recorder, First Engineer Sgt. Keith E. Hamilton still remembers this well!) I don't remember much of the getting to, or getting into the Cat, except that it was very hard for Mendish, because of the pain from his smashed shoulder. After takeoff one of the rescue crew gave me a heavy white bread onion and cheese sandwich, - it tasted very good ! I don't remember eating or drinking anything while on the island. When the Japanese invaded Indonesia, they were postulating 'Freedom with Prosperity' for their little brown brothers in greater East Asia. Initially many Indonesians warmly welcomed the Japanese as a way of getting out from under the yoke of Dutch colonialism, but after a time, they realised that the Japanese were acting more like conquerors and occupiers, and that this 'Freedom' was losing it's glow. Our warm reception by the islanders, was certainly very much due to the Japanese taking their young men away as non- volunteer forced labourers. Fortunately for us, we were the beneficiaries of this changing attitude. From our Group, we were the first survivors of downed aircraft to get out of enemy territory. The Catalina is a very unique aircraft, capable of taking off and landing on the open ocean under reasonable circumstances, and with extended flight time etc. but a low cruising speed of much less than 100 Miles Per Hour, which makes it vulnerable to attack, and this slowness, with the extremely low operational altitude necessary on this operation, plus the complete lack of Intelligence data regarding the Japanese occupational activity in the area , made this rescue a very risky undertaking. Serua Island was 425 miles from the Cat's forward base at Darwin at this time, and 150 miles inside a chain of islands, Japanese occupied and based, running 1500-2000 miles from Java and Timor in the West, to New Guinea in the East. These Japanese controlled islands were a randomly scattered, loosely linked chain, with some of the islands overlapping in the East West direction. In the mid section, none are more than 20 East West miles apart, - a rather solid 'fence' that facilitated the enemy's control and observation, many miles out to sea. On this rescue mission, our Cat had to penetrate deep into enemy territory, in broad daylight, find us, land, retrieve us from the beach, - take off, and fly back, all the while under potential observation and/or attack. These gutsy Aussies personify the meaning behind the phrase, 'Comrades in Arms' ; - God bless Them ! Aid and cover support was furnished by Beaufighters in pairs, but they were at the limit of their range from their Darwin base, so for part of the mission, a pair of fighters took off every 20 minutes, in order to sustain the continuous 2 fighter cover. - Typical in war ; using equipment designed for different geography, a totally different war in Europe, where the English Channel is only 22-25 miles wide. |

|

Seroea Operations 20th. January 1944, and I as a member of the Catalina crew skippered by Flt. Lt. D. R. Lawrence , and being part of 11 Squadron's temporary deployment to Darwin, for ongoing operations in the mining of ports and channels in the Halmaheras area, a mines drop operation flight of 18 hours 20 minutes on the 14th., then a second mines drop of 18 hours 40 minutes on the 16th. we were now awaiting further instructions. We were having a rest day while our present aircraft A 24- 34, was being serviced on the water in Darwin harbour, even so this meant that as first engineer, I was required to be on call, and was on board checking the progress of the service, when a message came through from headquarters, that a Liberator, (serial No. 42-73117, 'Doodlebug') from the American Darwin based 380 th. Bomb Group, had crash landed at sea in the vicinity of a small native inhabited volcanic island 400 odd miles north of Darwin, on the return from the previous day's bombing operation in the vicinity of Ambon. Catalina A-24-54 from our Darwin detachment, captained by Sqdn. Leader W.K. Bolitho had already been despatched to the area to undertake the rescue, accompanied by a 380th Liberator for support during the journey, as the crash zone was well into Japanese held territory at this time, the object being to rescue any American crew survivors which had been seen swimming towards land, this observed by a support B24 that had lingered in the area at the time of the crash, but had to leave because of low fuel reserves. They had dropped life vests and a life raft to the swimmers, before departing the area, but as it later turned out, rough seas had prevented the swimmers from seeing them, -- but there were survivors! Unfortunately the first rescue attempt was

thwarted because of extremely rough seas in the area, Sqdn. Ldr.

W.K.Bolitho who was a very experienced skipper, in A24 - 54, deciding that

conditions were far too dangerous to attempt a landing, - let alone taking

on board injured men and taking off again, but he and his accompanying

American B 24 escort, were able to note that natives on the island were

waving and appeared to be friendly. The Skipper had, as soon as he knew of the problems, travelled to the local strip and requisitioned Beaufighter A 19 - 160, and a pilot to fly him out to the crash site and reconnoitre the area and check conditions, which he judged to be easing, with better conditions possible in the next few hours. The weather report seemed to confirm this. This recce flight was 'legalised' by the Beaufighter pilot carrying out a normal sweep of the area to check on possible Japanese movements. For the first hour or so of our flight, we were in night time conditions and flying right down almost at sea level, this to foil any Japanese radar warning of our approach, but later as we neared the crash area, our Beaufighter escorts appeared, changing at intervals, until as we approached the island of Seroea, now in broad daylight, the Beaufighters who were operating at the end of their range, were of necessity changing over every 20 minutes, and so it was that we finally sighted the small plume of volcanic smoke arising from the rugged upthrust of volcanic rock that was the remains of the once enormous volcano, and now we hoped, the refuge of the surviving members of the Liberator's crew. We flew along the high ocean flank of the old volcano, with it's sheer rock face towering above us to the smoking vent at it's crest, and plunging almost vertically into the sea, we then turned 180 Degrees to port around it's Eastern (?) extremity, and found ourselves flying over a large semi-enclosed area of sea, surrounded by the odd crags of volcanic rock standing clear of the ocean, that had once been the sides of the huge caldera of this ancient volcano. By now the last of our escorts were leaving the area, and we were on our own, and our Navigator Stewart Ikin, was signalling with our Aldis Lamp in the general direction of what appeared to be a small native settlement down close to the rocky shore, where we assumed any survivors would be, -- as it turned out, correctly. We had no idea if they could understand our message, and they could only wave a reply, the message being as I recall, R-U-O-K , which was of course 'Are you OK' At this point we had no idea if in fact they were already being held prisoner, and all the Catalina's guns were being held at the ready, in case of enemy fire, but as it happened, all signs appearing from the village seemed to be friendly, and we did a circuit inside the huge area of the surrounding peaks thrusting up from the ocean, and did a normal rough water landing, the sea still running moderately high. As soon as the aircraft had come to rest, our crew members re- manned their guns, and we anchored as close in to the rocky shore as we dared, on what we gathered to be a small area of sandy bottom, the possibility of attack from the shore was still high in our minds, - but it wasn't long before canoes were launched into the sea from the village, and soon we were surrounded by canoes and chattering excited villagers, and by signs passed back and forth, it soon became apparent that they had rescued and treated 5 survivors for their injuries as well as they could, and after some preparation, the Americans were being ferried out to us by a large canoe, three of them being in a rather bad state, but all obviously pleased with their rescue. Some form of English/Dutch verbal contact had been made with one of the natives in a canoe, and after some time we had several of the locals on board, one the son of the local Chief, and it was arranged that we should fly him and 3 others back with us to Darwin with the purpose of them giving information of the local enemy conditions to the Dutch and Australian intelligence, Seroea and the other islands in the area having been Dutch possessions before the arrival of the Japanese. It was also made known to them that their 'holiday' in Australia, would only be a matter of a few weeks, and that we would then return them to their island home. In retrospect one must believe that we were very persuasive, or they were happy to get the opportunity to be away from Japanese occupation, which had seen most of the male population removed from Seroea and other inhabited islands, almost certainly to slave labour elsewhere, this occurring during the irregular visits of a patrol boat, at which time most of the residents would go into hiding amongst the surrounding crags after hiding their canoes, possibly sinking them and filling them with the plentiful local rocks. With the possibility of one of these visits, we were soon all settled aboard, and taking off for the return flight to Darwin, our passengers having their first taste of life in the air! One of the first jobs after getting the badly injured crew members settled in the Catalina's bunks, was to organise some food for them, and I remember making cheese and onion sandwiches, and anything else that I could scrounge in the galley, to feed guys that had apparently had nothing to eat since their unfortunate arrival on Seroea, the local medical ministrations, and the fact that they had been lying out in the open, in very rough, - but warm conditions for quite some time, hoping that their plight had been recognised, and rescue was on the way, they having previously heard the Beaufighters in the area, but having no idea as to whether they were friend or foe, their waiting hours had been uncertain and stressful to say the least, their only consolation being that the natives were very friendly and caring towards them. Our flight back to Darwin was an uneventful but very happy one, and the harbour mining operations now being finished for the present time, the next morning we were returning to Cairns in A24-34, via Melville Island where we were required to check out the status of A 24 - 56 skippered by Flt. Lt. Bill Minty, which had lost most of it's fabric wing and control surfaces as a result of an accidental fire while refuelling from drums. Our rescued crew members were installed in the Darwin hospital, the 2 severely injured later being repatriated to the USA, where they recovered , some of the survivors later returning to duty. As for us, it was back to normal operations until about 3 weeks later, when we were given a few days restricted leave, and now flying A 24-55 we departed for Brisbane and the Australian Dutch intelligence unit where we were made very welcome and treated to a lavish dinner, and were each presented with a Dutch 'commando' weapons and survival kit, ( only daggers and bush knives, - no guns !). Then we flew to Bowen for a few more days of official R and R, while A 24 55 underwent a major service, and on the 11th. February, '55' was once again heading for Seroea via. Brisbane and Darwin, this time with the returning islanders, now decked out in new clothes by the Dutch authorities, after their 2 weeks spent answering questions, and enjoying the sights of Brisbane and Australian and Dutch hospitality. Also on board were Dutch intelligence officers and an interpreter, who , if the island proved to be free of Japanese occupation, were to spend one night ashore, talking to the island elders, with a view to establishing some form of intelligence operation, and thanking them both formally and financially for their help with the crash survivors. This operation taking place on the 13th. and 14 th. February. It appeared that our Intelligence had worked out a rough schedule of the possible Japanese visits, and even if by some chance the Japanese intelligence had learned of the rescue , and had installed some form of opposition on Seroea , it would become very apparent to us upon our second arrival, simply because there was no real jungle or tree cover for a body of men and their equipment on the small habitable area that was present. Even so, we were well prepared, should our arrival result in armed opposition. So it was that February the 13 th. at 3.15 in the afternoon, saw A 24 - 55 lift off the waters of Darwin harbour, and a little over 4 hours later we were anchored well off shore at Seroea, with a flotilla of canoes heading out to welcome the local men back home, and to take the intelligence men ashore for the night. A schedule of watches had already been worked out, and so 2 members of the crew, one up on top of the mainplane with a light machine gun, and the other keeping watch at one of the Cat's .5 Brownings in the shore facing 'blister', the watches to be changed every 2 hours, the rest of the crew settling down to an uneasy sleep. As the First Engineer, I took an early watch up on the mainplane, but can't remember sleeping at all throughout the night, as It was my job to be ready to start the engines in the event of an attack, and we were to be ready to get the anchor up and take off the moment all were on board. I later thanked God that this had never become a reality, as in the early daylight next morning while we waited for the canoes to put out from shore with the returning officers, and with '55' ready for immediate start up, I and the second pilot, Flying Officer Ron Wise, decided that there was time to have a morning swim in the now calm crystal waters of the old caldera, and this we did amongst the ever present canoes of the villagers, with them warning us of the 'big fish' which it later turned out were not sharks, - but giant barracudas! However, when the bow man later tried to raise our folding stainless steel anchor, with all on board, and me ready to start the motors, he found that the anchor was really anchored into the jumbled volcanic rock, and all attempts to get it off the bottom failed and they were preparing to attempt to cut the stainless steel anchor cable, when I being still wet from my swim volunteered to swim down to the anchor and see if I could release it. So the second engineer was posted at the Engineer's control panel, and I climbed up on top of the wing, then a couple of the stronger crew members pulled the anchor cable up hard, bringing the aircraft as far forward as possible, and with instructions to let the anchor rope go slack soon after I made the bottom, then wait for a tug on the rope if I could manage to get the anchor released. I dived down and found the anchor down inside a crevice in the jumbled rocks, and with the anchor cable slack, I quickly released the anchor, and folded it up, and laid it on top of a flat rock, then tugged on the anchor cable and headed for the surface 20 or so feet above me. I was then hauled in through a blister and the second engineer had the motors running, and we were soon airborne. This proved to be our last operation with

11 Squadron, as upon our return to Cairns, our Skipper immediately

volunteered to fly A 24- 33, which had lost a port wing tip float

assembly, and sustained other easily repaired damage, in an accident with

a ship that had slipped it's moorings in Cairns harbour, and created havoc

when it drifted into the line of 'Cats' moored on the other side of the

river, sinking one and damaging others . So after some discussion, the loose damaged structure was removed, and with a skeleton crew aboard, and our Armourer 'Doc' Carter, our heaviest crew member, sitting on the end of the wing that still had a float, I started up '33' and we slipped the moorings, with a workboat and crew standing by in case of an emergency, the Skipper then manoeuvred into a stable take off position, then when all was ready, Doc. ran down the wing behind the running starboard motor and down over the rear hull and was helped in through the open blister, and we were off, me getting the remaining float up as soon as possible. Upon arrival at Bowen, we reversed the process and landed without incident, and were then idle for 3 days in the town, before another aircraft A24-77 was ready for the return trip to Cairns, the completion of it's overhaul having been delayed for a couple of days for some reason. At this point I was declared unfit for flying duties as a result of an ongoing inner ear infection, probably caused from flying with a cold or some such thing, and it had now become critical and I was given Post Operational leave and a posting to a non flying unit, but by the 28th June, I was back with Catalinas at Rathmines awaiting a new posting to the USA with a Catalina Ferry unit, in the meantime I flew training exercises with new crews at Rathmines, but suddenly my posting was changed to Tocumwal and I found myself a Warrant Officer and the senior Engineer Instructor on Consolidated aircraft once more, --- but sadly on ground based B24 Liberators, mainly in the class room, with my flying duties restricted to in flight instruction to incoming Flight Engineers. Thus I saw the war years out at a dusty strip on inland Australia, far from the Sea and Catalinas !. Note. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I'd like to thank Richard Gibbons, Keith E. Hamilton, Malcolm Bridges, Bill Burnett, Keith Hamilton and Meg Dunn for their assistance with this home page.

REFERENCE BOOK

"Marine

Section - the Forgotten Era of Men & Vessels

by Leslie R. Jubbs

"Shorts Aircraft (Kent) Volume II"

"Interview with Crew Members of A18-11 and a survivor of the MV Mamutu" - AWM S05254

Can anyone help me with more information?

"Australia @ War" WWII Research Products

|

© Peter Dunn 2015 |

Please

e-mail me |

This page first produced 28 May 2005

This page last updated 13 January 2020